Introduction

Few tools in the world of firearms have achieved the universal respect and versatility of the 12-gauge shotgun. From the duck blinds of North America to the trap fields of Europe and the armories of military and law enforcement agencies worldwide, the 12 gauge has earned its place as one of the most enduring and adaptable firearms ever developed. Its story is one of engineering refinement, sporting tradition, and practical service.

Origins of the 12 Gauge

The term “gauge” refers to the number of lead balls of bore diameter that collectively weigh one pound. In the case of the 12 gauge, twelve lead balls of the shotgun’s bore diameter (approximately .729 inches) equal one pound. This method of measurement dates back to 18th-century British gunmaking, when smoothbore muskets were evolving into more refined fowling pieces for hunting and sport.

Early shotguns were muzzleloaders, often custom-built for bird hunting and pest control. By the mid-19th century, advances in metallurgy and cartridge design—most notably the advent of the self-contained shotshell—transformed the shotgun into a reliable, reloadable firearm. Among various gauges available (including 10, 14, 16, and 20), the 12 gauge struck a practical balance between power, recoil, and shot capacity.

Rise in Popularity and Standardization

The 12 gauge became the most common shotgun bore by the late 19th century, largely due to the advent of industrial manufacturing and standardized ammunition. Winchester, Remington, and other American makers began producing 12-gauge repeaters and single-shots for hunters and sportsmen. The introduction of smokeless powder in the 1880s further enhanced its performance, offering cleaner shooting and improved velocity.

Its versatility was key: the same shotgun could be loaded with light birdshot for quail, heavier shot for ducks, or solid slugs for deer. This flexibility made the 12 gauge a staple across rural communities and a favorite among outdoorsmen.

The 12 Gauge in Service

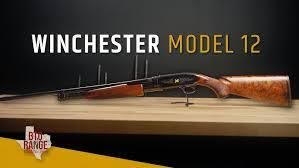

The 12 gauge also found a role in military and law enforcement service. During World War I, the U.S. military deployed the Winchester Model 1897 and Model 1912 “trench guns,” short-barreled 12-gauge pump-action shotguns fitted with bayonets and heat shields. Their effectiveness in close-quarters combat earned them respect—and, at times, notoriet

In law enforcement, the 12 gauge became a standard tool for riot control and close-range defense. Its ability to deliver both lethal and less-lethal ammunition (such as rubber pellets and bean bags) made it adaptable for a variety of public safety roles.

The 12 Gauge in Sport

Parallel to its service history, the 12 gauge became deeply ingrained in the world of competitive shooting. Sports like trap, skeet, and sporting clays flourished in the 20th century, with the 12 gauge at their center. Its wide pattern, manageable recoil, and consistent performance made it ideal for breaking fast-moving clay targets.

Prestigious events, such as Olympic trap and skeet, often feature the 12 gauge, underscoring its continued relevance in precision sports shooting. Hunters, too, continue to rely on it for waterfowl, upland birds, and even larger game, thanks to advances in non-toxic shot materials and improved choke designs.

Conclusion

From its 19th-century beginnings to its 21st-century refinements, the 12 gauge has stood the test of time. Whether in the hands of a sportsman, a soldier, or a competitive shooter, it represents a unique blend of heritage and innovation—a firearm that has shaped, and continues to shape, the world of shooting.