Introduction:

Subsonic and supersonic ammunition are two fundamental types of rounds that differ primarily in their velocity relative to the speed of sound, which is approximately 1,125 feet per second (fps) at sea level. The differences in velocity have a cascading effect on a round’s sound, recoil, and point of impact (POI

1) Key definitions (short)

- Speed of sound (Mach 1): ≈ 343 m/s at sea level, 20 °C (this value changes with temperature and altitude).

- Subsonic: projectile muzzle velocity below speed of sound.

- Supersonic: projectile muzzle velocity above speed of sound.

- POI (Point of Impact): where the bullet actually strikes relative to where the sights are zeroed.

- Recoil momentum & energy: two related measures — momentum (mass × velocity) affects impulse; kinetic energy (½ m v²) relates to felt energy transfer tendencies. Gas blowback from propellant also affects recoil.

2) Sound (what you hear)

- Supersonic: produces the muzzle blast plus a sonic crack created by the projectile traveling faster than sound. That crack is typically the dominant perceived sound at medium/long range and cannot be removed by a suppressor if the bullet itself is supersonic (suppressors reduce muzzle blast but not the supersonic crack).

- Subsonic: no sonic crack. With a suppressor, muzzle blast can be greatly reduced — resulting in a much quieter overall signature. Ambient conditions (wind, range, terrain) still matter.

Practical note: even subsonic loads can be loud if the powder/primer produces significant muzzle blast; a subsonic load + suppressor typically gives the most noticeable reduction in perceived sound.

3) Recoil — qualitative and quantitative view concepts

- Momentum (p) = m × v. Recoil impulse is primarily related to the momentum of the bullet (plus escaping gases).

- Kinetic energy (KE) = ½ m v². Energy scales with the square of velocity — so small velocity increases produce larger energy increases.

Example calculation (step-by-step arithmetic)

We show a clear numeric comparison using plausible, easy-to-follow numbers. These are illustrative only to show the relationships.

Choose a projectile mass of m = 0.010 kg (10 grams ≈ 154.3 grains — a realistic midweight bullet for demonstration).

- Supersonic example velocity: v_sup = 400 m/s (this is > speed of sound 343 m/s, so supersonic).

- Subsonic example velocity: v_sub = 300 m/s (this is < 343 m/s, so subsonic).

Momentum p = m × v

- Supersonic momentum:

- m = 0.010 kg

- v_sup = 400 m/s

- p_sup = 0.010 × 400

- = 4.0 (units: kg·m/s)

- Subsonic momentum:

- m = 0.010 kg

- v_sub = 300 m/s

- p_sub = 0.010 × 300

- = 3.0 (units: kg·m/s)

Conclusion from momentum: supersonic round carries 4.0 vs subsonic 3.0 — i.e., supersonic momentum is 33.3% higher (because 4.0 / 3.0 = 1.333…).

Kinetic energy KE = ½ m v²

- Supersonic KE:

- KE_sup = 0.5 × 0.010 × 400²

- 400² = 160000

- 0.5 × 0.010 = 0.005

- KE_sup = 0.005 × 160000

- = 800 (units: joules)

- Subsonic KE:

- KE_sub = 0.5 × 0.010 × 300²

- 300² = 90000

- 0.5 × 0.010 = 0.005

- KE_sub = 0.005 × 90000

- = 450 (units: joules)

Conclusion from energy: supersonic KE is 800 J vs subsonic 450 J — supersonic has ≈78% more kinetic energy (800/450 ≈ 1.777…).

Conclusion from energy: supersonic KE is 800 J vs subsonic 450 J — supersonic has ≈78% more kinetic energy (800/450 ≈ 1.777…).

Practical recoil implication: because momentum increases ~33% and energy increases ~78%, supersonic loads generally produce more mechanical recoil and tend to transfer more energy to the firearm. In many firearms, felt recoil correlates more with impulse (momentum and gas), but energy differences magnify perceived sharpness of recoil.

4) POI shift and trajectory differences

Why POI shifts occur

- Different muzzle velocities change time of flight to any given range. Gravity acts during this flight time and drops the bullet; a slower bullet has longer time aloft → greater drop → different POI at target ranges.

- Ballistic coefficient (BC) and aerodynamic stability also matter: lower velocities change how a bullet decelerates and may increase sensitivity to wind.

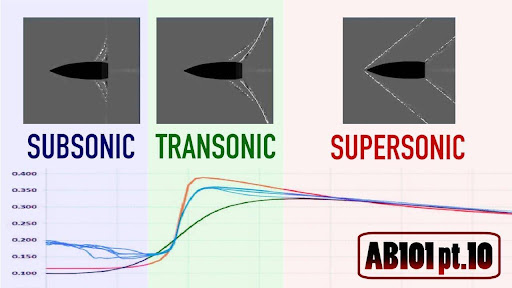

- Bullets crossing the transonic region (roughly Mach 0.8–1.2 depending on bullet shape and conditions) can experience destabilizing aerodynamic effects and increased vertical dispersion.

Example numeric POI comparison (step-by-step)

Using same m and velocities as above, compute vertical drop to 100 meters (pure ballistic simplification: assume flat fire with no initial vertical component, ignore air resistance for demonstration of time-of-flight effect).

- Gravity g = 9.81 m/s².

Time-of-flight t = range / velocity.

Supersonic at v_sup = 400 m/s:

- t_sup = 100 / 400

- = 0.25 s

Vertical drop d_sup = 0.5 × g × t_sup²

- t_sup² = 0.25² = 0.0625

- 0.5 × g = 0.5 × 9.81 = 4.905

- d_sup = 4.905 × 0.0625

- = 0.3065625 m → ≈ 30.7 cm

Subsonic at v_sub = 300 m/s:

- t_sub = 100 / 300

- = 0.333333… s

Vertical drop d_sub = 0.5 × g × t_sub²

- t_sub² = (1/3)² = 1/9 ≈ 0.111111…

- 0.5 × g = 4.905 (same as above)

- d_sub = 4.905 × 0.111111…

- ≈ 0.544999… m → ≈ 54.5 cm

POI difference at 100 m: 54.5 cm − 30.7 cm = 23.8 cm (≈ 9.4 inches). That is a substantial vertical shift and will be obvious on target.

Real world note: aerodynamic drag reduces velocities over flight so actual drop calculations should use full ballistic tables (BC + drag model). Still, the example highlights that switching between subsonic and supersonic loads without re-zeroing will often produce tens of centimeters/inches of POI shift at common ranges.

5) Transonic effects and accuracy

- Bullets that transition through transonic speeds can suffer yawing, increased dispersion, and POI inconsistency. This makes mid-range (where bullet slows from supersonic to subsonic in flight) a tricky zone for consistent precision.

- Subsonic loads avoid the supersonic→subsonic transition because they start below Mach 1; this can make them more consistent inside their effective range but with shorter effective range overall

6) Practical considerations & trade-offs

- Use-case: suppressed close-range work / stealth / reduced noise

- Subsonic + suppressor typically best for noise reduction and eliminating the sonic crack.

- Expect lower effective range and a large POI difference vs supersonic.

- Use-case: hunting or long-range shooting

- Supersonic preferred for flatter trajectory, higher retained energy, and extended effective range.

- Beware of the sonic crack for noise and possible fragmentation/terminal behavior differences.

- Autoloading firearms / cycling

- Subsonic loads often produce less gas pressure — can cause cycling issues in some firearms. Gas system tuning or heavier springs may be required.

- Consistency

- Factory match supersonic or handloaded subsonic loads can be made very consistent; the round-to-round consistency matters more than supersonic/subsonic label for precision

7) Recommendations for shooters (testing & deployment)

- Decide primary mission (suppression vs. range & energy). Choose load accordingly.

- Zero separately. Zero your firearm with the exact load you plan to use—do not assume supersonic zero will carry over to subsonic.

- Document POI differences. At set distances (25 m, 50 m, 100 m, and any operational distances) record POI for both loads.

- Measure velocities. Use a chronograph if possible — store muzzle velocities and standard deviation (ES) for each load.

- Test cycling reliability. If using an autoloader, test 200+ rounds of the intended subsonic load to verify reliability or tune gas/return springs.

- If noise matters, pair subsonic loads with a suppressor and measure perceived noise at shooter and downrange positions.

Watch for transonic zone. If you rely on targets at distances where the bullet will go transonic, test for POI shift and grouping—consider choosing loads that avoid or stay supersonic past the engagement envelope.

8) Short checklist for creating a load comparison test

- Chronograph readings: muzzle velocity (mean) and standard deviation for each load (≥10 shots).

- Grouping test: 5-shot groups at 25 m, 50 m, 100 m. Record POI and group size.

- Sound measurement: subjective and, if possible, dB meter at muzzle and 10 m.

- Function test: 200-round reliability test for semiautos (or an appropriate number for your platform).

- Environmental notes: temperature, altitude, wind, suppressor/no suppressor used.

Sound — real-world numbers and what they mean

- Peak levels for unsuppressed firearms. Typical unsuppressed rifle shots

commonly measure in the 150–170+ dB range at the shooter’s ear

depending on caliber and barrel length; pistol/22 levels are lower. The

supersonic sonic crack itself can produce a strong peak that is heard

downrange and is essentially unaffected by a suppressor because it is

produced by the bullet in flight. - Suppressor effect (typical). Modern rifle/centerfire suppressors commonly

reduce peak sound by ~20–40 dB depending on caliber, ammunition, barrel

length and suppressor design. That reduction is substantial (changes

perceived loudness a lot) but does not make a supersonic round silent —

the sonic crack remains if the bullet is supersonic. - Subsonic + suppressor outcome. A subsonic load fired through a good

suppressor typically produces the lowest peak levels for that firearm —

numbers reported for suppressed subsonic rifle/small-bore combinations

commonly fall into ranges that are still loud (e.g., roughly 108–135 dB in

many test reports) but are much quieter than unsuppressed supersonic

shots. Exact dB depends a lot on ammo and test setup.

Conclusions

- Sound: subsonic + suppressor = clearly quieter; supersonic always makes a sonic crack.

- Recoil: supersonic generally produces higher recoil momentum and much higher kinetic energy (energy grows with v²). Expect supersonic to feel snappier and often more forceful.

- POI shift: expect significant POI differences at common ranges; always re-zero and test for your exact load. Transonic transition can cause additional in-flight instability.