Introduction

If you’ve ever wondered what makes a bullet fly straight and true, the answer is not as simple as pulling the trigger. Long-range accuracy and even consistent performance on the hunting field depend on a critical, often-overlooked factor: barrel twist rate. This isn’t just a technical specification for gun manufacturers—it’s the single most important detail that connects your rifle to your ammunition.

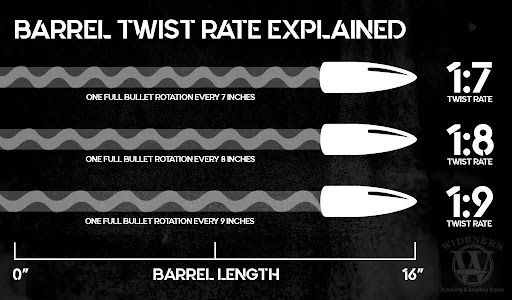

A barrel’s twist rate, expressed as a ratio like 1:9 or 1:12, indicates how quickly the spiral grooves (rifling) inside the barrel spin a bullet. A faster twist rate, with a lower number, causes the bullet to spin more aggressively. A slower twist, with a higher number, results in less spin. This rotational stability is what prevents a bullet from tumbling end over end and ensures it flies point-first to its target.

The wrong pairing of bullet weight and twist rate can be a disaster for accuracy. A bullet that doesn’t spin fast enough may yaw or “keyhole” its way to the target, creating an elongated hole. Conversely, a bullet that spins too fast can experience excessive pressure and even disintegrate in mid-air.

This post will demystify barrel twist rates, explaining what they mean for shooters and how to select the right ammunition for your firearm. We’ll break down the common twist rates for popular calibers, giving you the knowledge to get the best possible performance from your rifle.

What “twist rate” actually means

Notation: 1:9″ means the rifling makes one full rotation in 9 inches of barrel.

Effect: Spin stabilizes the projectile gyroscopically. Too little spin = unstable bullet (keyholing, poor groups). Too much spin rarely destroys accuracy but can slightly affect some long-range bullets.

What determines needed twist: bullet length and diameter, muzzle velocity, and bullet shape. Heavier bullets are usually longer, so they typically need faster twist

A simple rule of thumb

- If you plan to shoot short/light bullets (plinking, light match/hunting bullets), a slower twist (1:10–1:12 or 1:16 for rimfire) is usually fine.

- If you want to shoot long/heavy bullets (long-range, high-BC hunting bullets), choose a faster twist (1:7–1:9 for many rifle cartridges).

- When in doubt, follow the barrel manufacturer’s recommendation or pick a slightly faster twist if you expect to use heavy bullets.

Quick sign your twist is wrong

- Keyholing (bullet hits target sideways) — under-stabilized.

- Tight groups with weird vertical dispersion — could be over-stabilization interacting with bullet design or barrel harmonics, or simply an ammo/barrel mismatch.

- Consistent POI shift when switching bullet weights — expected; heavier or longer bullets often shift POI.Handy, practical examples by popular calibers

These are common, practical twist choices and what bullet weights they generally support. These are guidelines — test in your rifle.

- .22 LR

- Common twist: 1:16″

- Works well for typical .22 LR bullets (30–40 gr).

- .223 Rem / 5.56×45

- Common twists: 1:12″, 1:9″, 1:8″, 1:7″

- General guidance:

- 1:12 — good for lighter bullets (approx. 40–55 gr).

- 1:9 / 1:8 — versatile mid-range (approx. 55–69 gr).

- 1:7 — needed to stabilize the longest/heaviest factory bullets (69–80+ gr, long high-BC bullets).

- 6.5 Creedmoor / 6.5mm cartridges

- Common twists: 1:8″ to 1:8.5″ (some 1:7.7 or 1:7.9)

- Designed to stabilize long, high-BC bullets (120–147 gr and heavy long-range bullets).

- .308 Win / 7.62×51 NATO

- Common twists: 1:10″, 1:11″, sometimes 1:12

- 1:12 stabilizes lighter 147–150 gr bullets; 1:10 is a good all-around choice for heavier 168–190 gr match/hunting bullets.

- .30-06 Springfield

Common twist: 1:10″ (works well for most hunting and match bullets across typical weight ranges).

.300 Winchester Magnum / .300 WM

- Common twist: 1:10″ (needed to stabilize long, heavy .30-caliber magnum bullets at long range).

.338, .375, magnums (big game rounds)

- Twists vary, often 1:10″ down to 1:8″ depending on bullet length/BC — manufacturers match twist to the heavy bullets intended.

Handgun rifle-like examples (e.g., .357/.38)

- Typical handgun rifling twists vary (1:14–1:20) depending on design and bullet type; pistols rarely need the very fast twists rifles use.

A short technical note (Greenhill formula — simple estimate)

If you want a rough calculation, the classical Greenhill formula gives an approximate twist based on bullet diameter and length:

Twist (inches per turn) ≈ (C × D²) / L

Where:

- D = bullet diameter in inches

- L = bullet length in inches

- C = 150 (use 180 if muzzle velocity is high > ~2,800 fps)

This is a rough estimator. Modern stability formulas (Miller stability formula) are better but more complex. For practical shooting, trust manufacturer recommendations and field testing.

Practical advice for choosing a twist

- Decide what you’ll mostly shoot. Match the twist to the bullets you plan to use most.

- Check the barrel marking (often stamped on the barrel: 1:9 or 1:10) and the manufacturer specs.

- If you want versatility and expect to shoot heavy match bullets, choose a slightly faster twist rather than slower. A fast twist stabilizes light bullets too in most cases.

- Test your ammo. Even with the “right” twist, every barrel prefers specific loads. Try 3–5 different bullet types/weights and test groups at relevant ranges.

- For precision/long-range builds, care about bullet length/BC more than grain. Long high-BC bullets need faster twist.

Field-testing checklist (do this after picking a barrel/ammo)

- Fire a 5–10 round break-in or warmup sequence if the barrel is new.

- Shoot groups (3–5 shots) with your intended bullets at practical distances (100–300 yards for rifles).

- Observe for keyholing or poor groups — if present with long bullets, you likely need a faster twist.

- If performance is poor across all loads, consider trying other brands or twist rates if possible.

Deeper Information: Barrel Twist Rates Made Simple

Why bullets need spin in the first place

A bullet is not perfectly aerodynamic. It wants to tumble in flight because air pressure is uneven on its surfaces. Rifling grooves cut into the barrel force the bullet to spin. This spin creates gyroscopic stability, just like a spinning top that stays upright. Without enough spin, a bullet wobbles and eventually tumbles.

What happens when spin is wrong:

- Understabilized: keyholes, wild groups, unpredictable trajectory.

- Overstabilized: usually still accurate but may reduce long-range consistency with some bullet designs because the nose struggles to follow the arc of flight.

Most shooters worry only about understabilization. That is the one that ruins accuracy.

Why bullet length matters more than bullet weight

Shooters often say:

“Heavier bullets need faster twist.”

The truth:

Longer bullets need faster twist.

Weight is just a quick and dirty way to guess length. Modern bullets prove this:

- Two bullets can be the same weight but different shapes.

- Longer shapes (like very low drag or boat-tail designs) always need faster twist, even if the weight is moderate.

- Example:

- A 62 grain FMJ 5.56 bullet is shorter than a 62 grain solid copper bullet.

- The copper bullet needs a faster twist even though weight is identical

The role of velocity

Spin rate is a product of twist rate and muzzle velocity:

- A fast-moving bullet spins faster in the same twist barrel.

- A short barrel means lower velocity, which reduces spin rate.

So carbines often favor faster twists than full-length rifles in the same caliber.

Example:

- A 16″ AR-15 with 1:7 twist is better for stabilizing long/heavy bullets than a 20″ rifle with 1:12 shooting at lower velocity.

Twist rate and barrel wear

This isn’t a big deal for most shooters, but:

- Fast twist barrels can experience slightly higher friction and wear.

- High pressure + fast twist barrels (like 6.5 Creedmoor) may have shorter barrel life compared to slower twist and lower pressure cartridges.

- Still, barrel wear is dominated by heat and pressure, not twist alone.

Special cases: bullets that break the rules

- Short, light, varmint bullets: too much spin can cause jacket separation at very high speeds. Rare with modern construction but still possible in extremes.

- Armor-piercing and monolithic bullets: these are longer for the same weight and require faster twist.

- Subsonic bullets: often heavy and long but moving slowly, so need faster twists. Example:

300 Blackout subsonic loads (200–220 gr) require 1:7″ or 1:8″ twist despite low velocity.

Big picture examples by category

Varmint / high-velocity rounds

- .204 Ruger: 1:10″ or 1:12″ for 32–40 gr bullets

- .22-250: 1:12″ for varmint bullets, newer rifles 1:8″ for heavier long-range bullets

Mid-caliber standard rifles

- 5.56/.223: 1:7″ to 1:12″ based on bullet length

- .243 Win: 1:9″ for 80–100 gr hunting bullets

Long-range precision rifles

- 6.5 Creedmoor: 1:8″ for 120–147 gr bullets

- .300 PRC: 1:8.5″ or faster for 200+ gr long-range bullets

Handguns

- Twist rates vary widely and matter less due to short distances.

- Most pistol rounds are naturally short bullets, easy to stabilize:

- 9mm: often 1:10″

- .45 ACP: often 1:16″

- .44 Magnum: around 1:20″

How manufacturers choose twist

Companies design twist rates to work with the ammo they expect buyers to shoot. For example:

- Modern AR-15 barrels often use 1:7″ or 1:8″ because heavy match and defense bullets are common.

- Vintage rifles often have slower twists sized for older bullet designs.

How to diagnose a twist mismatch at the range

You may notice:

- Holes are shaped like ovals = slight yaw

- Full sideways impacts = full keyholes

- Groups shift drastically when switching bullet weights = marginal stability

- Good performance at 100 yds but falls apart at 300 yds = borderline stability

Rule:

If bullets fly fine at 100 but destabilize at distance, twist is almost fast enough but not quite.

Real takeaways for shooters

- Don’t pick a barrel just because someone online says it’s “better.”

- Pick based on the bullets you actually plan to shoot.

- Faster twist gives more flexibility and rarely hurts anything.

Final quick summary

If you remember only three things:

- Length drives twist: longer bullets = faster twist.

- Mission first: choose twist for the bullets that match your purpose.

- Test your ammo: every barrel has favorites.

Final practical takeaways

- Twist rate controls stabilization; choose it to match the length of bullets you plan to shoot.

- Faster twist = better for long, high-BC bullets; slower twist = fine for short/light bullets.

- When building or buying, prioritize the twist that fits your mission: plinking, hunting, or long-range precision. Test in your rifle; real-world performance beats theory.

Conclusion

Understanding rifle barrel twist rate is crucial for any shooter who desires precision. The right twist rate not only enhances bullet stability but also significantly impacts accuracy and performance. By recognizing how rifling influences bullet spin and factoring in elements like bullet weight and caliber differences, you can make informed choices that elevate your shooting experience. Remember, whether you’re a hunter or a competitive shooter, optimizing your twist rate is essential in achieving the best results. So, take the time to evaluate your rifle’s specifications and ensure that you’re set up for success on your next outing. If you’re ready to enhance your shooting skills, consider seeking professional advice to find the perfect twist rate for your needs.