Introduction

This report explains, in practical and non-political terms, the essentials of 12-gauge shot sizes, wad choices, and pattern behavior for two common uses: clay target shooting (sporting clays, skeet, trap) and field use (upland birds, waterfowl, general wingshooting). It’s written for shooters who want clear, usable knowledge — what each choice does, why it matters, and how to think about tradeoffs when selecting ammo.

Quick overview (the short read)

- Shot size determines pellet count, pellet energy, and how the pattern behaves on target. Smaller shot (higher numbers, e.g., 8, 9) = more pellets, lower individual pellet energy; larger shot (low numbers, e.g., 2, BB, #1) = fewer pellets, higher energy.

- Wads separate powder from shot, cushion recoil, and strongly influence pattern density and uniformity. Modern wads are engineered to control shot deformation and dispersion.

- Pattern means how pellets are distributed on the target face at a given distance. Pattern is affected by shot size, shot material, wad design, velocity, choke, and the shell’s manufacturing quality.

- Clay shooters and field shooters prioritize different outcomes: clays demand dense, even patterns at moderate ranges; field work often needs pellets with more retained energy and consistent patterns at varied distances.

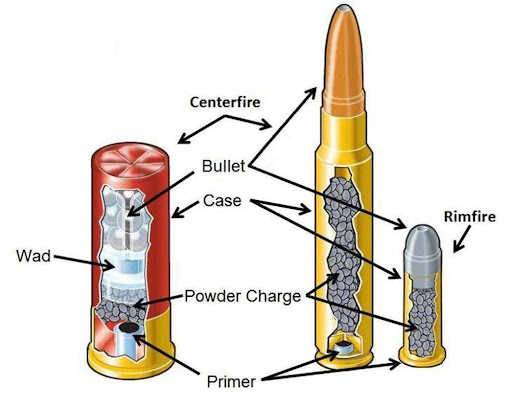

Anatomy of a 12-gauge shotshell (brief)

A typical modern 12-gauge shotshell contains:

- Hull / case — usually plastic with a brass head.

- Primer — ignites the powder charge.

- Powder — generates gas to propel payload.

- Wad — a polymer component (or fiber in older shells) that seals gas, cushions the shot, and separates shot from gas and barrel.

- Shot payload — pellets (lead, steel, bismuth, tungsten, or other alloys).

- Crimp or over-powder seal — closes the shell.

Each part influences patterning; wads and shot are the most directly relevant to patterns.

Shot sizes: what the numbers mean and practical implications

Shot sizes are designated by numbers (#) — larger numbers = smaller pellets. Common 12-gauge shot sizes for clays and field:

- #9, #8 — Very small pellets used in some skeet loads or pest control. Dense patterns, short effective range. Common in target loads for close-range clay targets.

- #7½, #7 — Typical skeet sizes and some sporting clays loads. High pellet counts increase the probability of breaking fast, close clays.

- #6 — Versatile for close to moderate clay work and some upland birds. Good balance of pellet count and energy.

- #5, #4 — Common for sporting clays and close-range upland work where slightly larger pellet mass helps.

- #3, #2, #1, BB, B, 0, 00 (double-aught) — Larger pellet sizes used for heavy field work (pheasant, duck when legal), deliver more energy per pellet, used at longer ranges or on bigger birds. Fewer pellets per shell.

Practical tradeoffs

- Smaller pellets: more pellets → more chances to hit a fast-moving small target like a clay. But each pellet carries less energy, so terminal performance at range drops quickly.

- Larger pellets: fewer pellets → lower probability of many pellet strikes on a small target, but a higher chance a pellet will penetrate or deliver lethal energy on larger birds or at longer ranges.

- Clays vs. field: clays favor more, smaller pellets for dense patterns; field work often favors larger pellets for retained energy and penetration.

Shot materials and their patterning quirks

While lead has historically been the standard, environmental rules and performance needs have increased the use of alternatives.

- Lead: dense, malleable, excellent patterning and energy. Still common where legal.

- Steel: less dense than lead, requires larger pellets to match energy; patterns and shot dynamics differ because steel is harder and less deformable, which can change spread and pellet flight.

- Bismuth / tungsten alloys: denser than steel and closer to lead performance; generally pattern more like lead and retain energy well.

- Effect on patterning: harder shot types (steel) tend to deform less and may deliver tighter or sometimes more erratic patterns depending on wad and choke; density affects pellet drop and energy.

Wads — why they matter more than many shooters realize

A wad performs several jobs: gas seal, cushioning, shot cup/confinement, and — crucially — influencing how pellets exit the muzzle.

Main wad types and effects

- Single-piece plastic wads (shot cup + cushion integrated) — Most common modern design. They control how shot columns leave the barrel and reduce pellet deformation. Different cut patterns and skirt designs change how pellets flare after exiting.

- Two-piece wads (cushion plus shot cup separate) — Offer better protection against pellet deformation at higher velocities and sometimes improved patterns with dense, hard shot.

- Fiber wads (older style) — Generally produce looser patterns and more pellet deformation; still used in some niche loads.

- Specialized wads — Engineered to center the shot column, reduce pellet-to-pellet contact, and manage dispersion for tighter patterns.

How wad choice affects pattern

- Shot deformation: softer shots (lead) deform when rammed and fired; wads that protect minimize deformation, preserving pellet sphericity and consistent flight.

- Shot stringing: wads that provide better confinement reduce initial sideways movement; this improves uniformity.

- Pattern density and shape: some wads promote tighter, more uniform patterns; others create a slightly larger, even spread.

Velocity and wad interaction

Higher velocity can increase pellet deformation and dispersion. The right wad offsets this by cushioning and keeping the shot column together until exiting the muzzle.

Patterns: what they are and why they matter

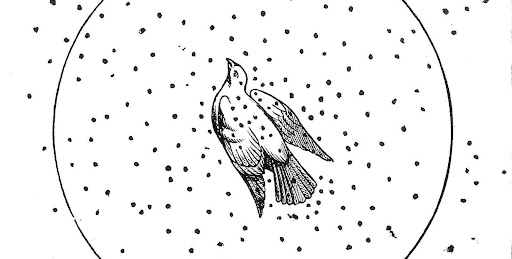

A pattern is the distribution of pellets on a target plane at a particular distance. Shooters think in terms of pattern density (pellets per square inch), uniformity (how even distribution is across the circle), and effective pattern diameter (how concentrated in the center).

Key factors shaping a pattern

- Shot size: smaller pellets give a denser-looking pattern for the same pellet count.

- Wad design: affects early spread and uniformity.

- Choke: governs constriction and therefore the rate of spread (see next section).

- Barrel length & forcing cone: influence initial velocity and shot exit behavior.

- Velocity & powder: higher speeds affect pellet deformation and can slightly widen patterns if not well-controlled by the wad.

- Manufacturing consistency: better-made shells generally pattern more predictably.

Choke and pattern relationship (short and practical)

Chokes control the amount of constriction at the muzzle and thus the rate at which a shot column opens up into a pattern. Common chokes range from Cylinder (no constriction) to Full (tight constriction).

- Cylinder / Improved Cylinder — Wide, fast-opening patterns. Ideal for close-range clays or flush-placed birds.

- Modified — Middle ground: effective for moderate clay distances and general field shots.

- Full — Tight patterns at longer ranges: used when you need a dense center at distance (certain trap distances, large game at longer range).

Interaction with shot size

- Smaller shot tends to open faster; tighter chokes may be used to keep the pattern dense on target.

- Larger pellets maintain more energy and sometimes benefit from less constrictive chokes to avoid excessive pellet deformation when forced through tight constriction (especially with hard shot like steel).

Clays vs. Field — how priorities differ

Clays (sporting clays, skeet, trap)

- Distances: generally short to moderate (skeet often under 25 yards; trap and sporting clays vary more).

- Priority: break the clay — dense, even patterns at the expected distance. Pellet count and even spread matter more than individual pellet energy.

- Typical choices: #8, #7½, #6 in target loads; wads that promote even, tight center patterns; target shot (often lead or high-performing alternative) optimized for minimal deformation.

Field (upland birds, migratory waterfowl — respecting local regulations and species)

- Distances: variable; shots can be close or extend to longer ranges depending on the species and terrain.

- Priority: retain energy and stop the bird — larger pellets or denser materials (e.g., #4 to 00, bismuth/tungsten where allowed) to ensure penetration and effectiveness at range.

- Typical choices: larger shot sizes for bigger species; wads that minimize deformation at higher velocities for better downrange performance.

Choosing the right load — practical guidelines

- Know your target and typical range:

- Clays at close range → smaller shot sizes for dense patterns.

- Upland birds at moderate range → mid-size pellets (#6 to #4).

- Bigger birds or longer shots → larger pellets (#3 to 00) and denser materials.

- Pair shot size with an appropriate wad:

- Target loads: shot cups and designs created for minimal deformation and even patterns.

- Field loads: wads engineered for clean release and retained pellet integrity at varied velocities.

- Match choke to load:

- Use a choke that delivers the pattern concentration you need at your typical engagement distance.

Consider shot material where regulations or performance needs dictate (e.g., steel for waterfowl in many regions). Adjust pellet size to account for density differences.

Patterning — how to evaluate without getting overly technical

A simple practical approach: choose a target distance representative of your use, shoot a sample group of shells with a chosen choke, and inspect the pattern for density and uniformity. What to look for:

- Center density — are pellets concentrated where the target would be?

- Edge uniformity — are pellets evenly spread or clumped?

- Pellet count in the hit zone — more pellets in the effective zone = higher chance to break a clay/disable a bird.

(That’s the concept — for specific patterning drills and step-by-step range procedures, consult a qualified instructor or range resources.)

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Using too-small shot at long distance — density may be okay, but pellets lack energy to be effective.

- Ignoring wad/shot material mismatch — hard steel through an unprotected wad can pattern poorly and damage the barrel over time.

- Relying on box labels alone — loads with the same shot size can pattern very differently depending on wad design, powder, and manufacturer. Test what you shoot.

- Assuming denser = better — for some clays, a slightly wider but evenly distributed pattern can break targets as well as a super tight center.

Strong closing (practical coach tone)

If you want consistent results, don’t leave ammo choice to guesswork or habit. Decide first what you’ll be shooting and at what ranges, then pick a shot size and material that gives the pellet energy you need. Match that to a load with a wad design proven for consistent patterns, and use a choke that yields the coverage you want at your typical distance. Above all — test. A half dozen shells through your gun will tell you more than the prettiest box label. Treat patterning as routine equipment care: small investments of time yield predictable, repeatable outcomes in the field and on the range. Stay safe, shoot responsibly, and let the data from your own patterning inform your choices going forward.